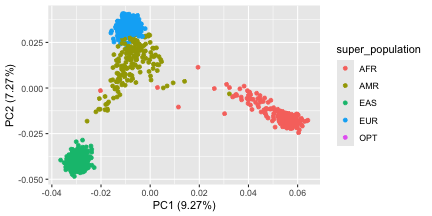

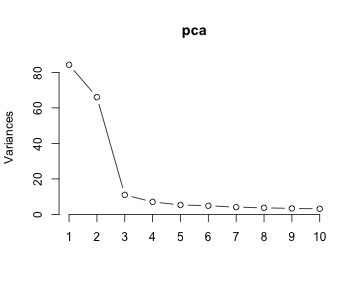

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide .title[ # Principal Components Analysis (PCA) ] .subtitle[ ## Applications in Genomics ] .author[ ### Mikhail Dozmorov ] .institute[ ### Virginia Commonwealth University ] .date[ ### 2025-11-19 ] --- <!-- HTML style block --> <style> .large { font-size: 130%; } .small { font-size: 70%; } .tiny { font-size: 40%; } </style> ## Big picture In general, most dimensionality reduction methods can be placed into one of two categories: **feature-mapping** approaches versus **distance-preserving** approaches. - Feature mapping approaches directly find a mapping function from the original, high-dimensional space to a low-dimensional space, subject to some optimization goal. A commonly used feature mapping technique is principal component analysis (PCA), which aims to find a linear transformation of a given set of features while preserving, as much as possible, the variance of the original data. --- ## Big picture In general, most dimensionality reduction methods can be placed into one of two categories: **feature-mapping** approaches versus **distance-preserving** approaches. - In contrast, distance preserving approaches project the data points to a low-dimensional space in which the original pairwise distances (or similarities) between pairs of data objects is preserved. MDS (Kruskal and Wish, 1977) is a canonical example of a distance-preserving approach. --- ## Big picture In general, most dimensionality reduction methods can be placed into one of two categories: **feature-mapping** approaches versus **distance-preserving** approaches. - A commonly used feature mapping technique is principal component analysis (PCA), which aims to find a linear transformation of a given set of features while preserving, as much as possible, the variance of the original data. --- ## Big picture In general, most dimensionality reduction methods can be placed into one of two categories: **feature-mapping** approaches versus **distance-preserving** approaches. - In contrast, distance preserving approaches project the data points to a low-dimensional space in which the original pairwise distances (or similarities) between pairs of data objects is preserved. - MDS (Kruskal and Wish, 1977) is a canonical example of a distance-preserving approach. --- ## Dimensionality reduction overview - Dimensionality Reduction (DR) essentially aims to find low dimensional representations of data while preserving their key properties - DR methods can be modeled after physical models with attracting and repelling forces (Force Directed Methods), projections onto low dimensional planes (PCA, ICA), divergence of statistical distributions (SNE family), the reconstruction of local spaces or points by their neighbors (LLE) .small[ Kraemer, et al., "dimRed and coRanking---Unifying Dimensionality Reduction in R", The R Journal, 2018 https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-039 ] --- ## Dimensionality reduction overview <img src="img/dr_classification.png" width="600px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .small[ Guido Kraemer, Markus Reichstein, and Miguel D. Mahecha, “DimRed and CoRanking Unifying Dimensionality Reduction in R,” The R Journal, 2018, https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2018/RJ-2018-039/index.html. ] --- ## What is PCA? * **Unsupervised learning method** - discovers structure without labels * **Linear dimensionality reduction technique** - embeds data into a lower-dimensional linear subspace * **Feature extraction method** - creates new variables from original features * **Well-studied multivariate statistical technique** - old but reliable <img src="img/pca_quick.png" width="300px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- ## Why use PCA? - Takes a group of variables (e.g., genes, SNPs) and looks for underlying structure - Constructs a low-dimensional representation that describes as much variance as possible - Finds a linear basis of reduced dimensionality in which variance is maximal .small[ https://setosa.io/ev/principal-component-analysis/ ] --- ## Why use PCA? - Helps understand if/how variables (genes) or observations (subjects) cluster together - Projects high dimensional data into 2-3 dimensions for visualization - Often captures much of the total data variation in a few dimensions (< 5) .small[ https://setosa.io/ev/principal-component-analysis/ ] <!--- ## PCA: Quick Theory - Eigenvectors of the covariance matrix - Finds orthogonal groups of variance - Ordered from most to least variance - Components of variation - Linear combinations explaining the variance - Performs a rotation that maximizes variance in new axes <div style="text-align: center; margin-top: 20px;"> <i>See: http://setosa.io/ev/principal-component-analysis/</i> </div> --> --- ## Notation **Data Matrix `\(X\)`:** `\(n \times p\)` matrix - `\(n\)` observations (samples, subjects) - `\(p\)` features (genes, SNPs) - Assume genes (columns) are centered: mean = 0 **Principal Component `\(Z_i\)`:** Linear combination of features `$$Z_i = \phi_{1i}X_1 + \phi_{2i}X_2 + ... + \phi_{pi}X_p$$` **Loading Vector `\(\phi_i\)`:** `\((\phi_{1i}, \phi_{2i},..., \phi_{pi})^T\)` - Elements `\(\phi_{ji}\)` are the **loadings** - Constrained: `\(\sum_{j=1}^p\phi_{ji}^2=1\)` (normalized) **Scores `\(z_{ni}\)`:** Projection of observation `\(n\)` onto component `\(i\)` ??? Before performing PCA, each gene (each column of `\(X\)`) should be **centered**, meaning the mean expression of each gene across samples is zero. Centering removes location effects so PCA focuses on **variation**, not absolute expression levels. Now, a **principal component**, `\(Z_i\)`, is just a **weighted linear combination** of the original features. The weight vector is the **loading vector**, denoted `\(\phi_i\)`. Each loading `\(\phi_{ji}\)` tells us *how much gene `\(j\)` contributes to principal component `\(i\)`*. To keep things properly scaled, we enforce a constraint: the loading vector has length 1. That is, all the squared loadings sum to 1. Finally, the **scores** `\(z_{ni}\)` are the values we get when we project each sample onto the `\(i\)`-th component. These represent the new coordinates of our samples in PCA space. --- ## Mathematical Foundation For random vector `\(\mathbf{X} = (X_{1}, X_{2},...,X_{p})\)` with covariance matrix `\(\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\)` and eigenvalue-eigenvector pairs `\((\lambda_{1}, \phi_{1}), (\lambda_{2}, \phi_{2}),...,(\lambda_{p}, \phi_{p})\)`: The `\(i\)`-th principal componentp: `\(Z_{i} = \phi_{1i}X_{1} + \phi_{2i}X_{2} + ... + \phi_{pi}X_{p}, \text{ for } i=1,2,...,p\)` Has the following properties: `\(Var(Z_{i}) = \phi_{i}^T\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\phi_{i} = \lambda_{i}\)` `\(Cov(Z_{i},Z_{k}) = \phi_{i}^T\boldsymbol{\Sigma}\phi_{k} = 0, \text{ for } i \ne k\)` ??? Consider the data as a random vector `\((X_1,\dots,X_p)\)` with covariance matrix `\(\Sigma\)`. PCA finds a set of **eigenvalues** and **eigenvectors** of this covariance matrix. Each eigenvector `\(\phi_i\)` becomes a **loading vector**. Each eigenvalue `\(\lambda_i\)` tells us **how much variance** is captured by the corresponding principal component. One of the properties of PCA is that the principal components are **uncorrelated**. In other words, the covariance between different components is zero. This tells us that PCA rotates the coordinate system so that each new axis captures a unique direction of variation, and these directions don’t overlap. --- ## Computing the First Principal Component **Optimization Problem:** `$$\max_{\phi_{11},...,\phi_{p1}} \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n\left(\sum_{j=1}^p\phi_{j1}x_{ij}\right)^2$$` subject to `\(\sum_{j=1}^p\phi_{j1}^2=1\)` ??? To understand how PCA works intuitively, it helps to look at the optimization problem it solves. The **first principal component** is the direction in feature space that captures the **maximum possible variance**. So we look for a loading vector `\(\phi_1\)` that maximizes the **variance of the projected data**: `\(\max_{\phi_1}\frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n(\phi_1^T x_i)^2\)` This simply means: *‘Find the direction onto which the projected samples spread out the most.’* But we add a constraint: the loading vector must have length 1. Without this constraint, the trivial solution would be to scale `\(\phi_1\)` infinitely. --- ## Computing the First Principal Component **Solution via Eigendecomposition:** PCA solves the eigenproblem: `\(Cov(X)M = \lambda M\)`, where `\(M\)` is a matrix of eigenvectors The solution is given by the dominant eigenvectors of the covariance matrix: `$$C_v = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^n x_i x_i^T$$` The problem can be solved via **singular value decomposition (SVD)** of matrix `\(X\)` ??? From linear algebra, this maximization problem is equivalent to finding the **dominant eigenvector** of the covariance matrix. The covariance matrix of the data is: `\(C = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{i=1}^{n} x_i x_i^T.\)` When we compute the eigendecomposition of `\(C\)`, the **eigenvector with the largest eigenvalue** is our first principal component direction. In practice, especially when `\(p\)` is large, we use a more numerically stable method: **singular value decomposition**, or SVD. SVD decomposes the data matrix directly, and PCA is essentially a by-product of this decomposition. This is why tools like `prcomp()` in R use SVD behind the scenes. --- ## Singular Value Decomposition <img src="img/svd.png" width="800px" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> .small[ https://research.facebook.com/blog/2014/9/fast-randomized-svd/ ] --- ## PCA for gene expression - Given a gene-by-sample matrix `\(X\)` we decompose (centered and scaled) `\(X\)` as `\(USV^T\)` - We don’t usually care about total expression level and the dynamic range which may be dependent on technical factors - `\(U\)`, `\(V\)` are orthonormal - `\(S\)` diagonal-elements are eigenvalues = variance explained ??? In gene expression analysis, PCA starts with a gene-by-sample matrix, which we always center and scale first because genes differ greatly in average expression and variance. The matrices `\(U\)` and `\(V\)` are orthonormal, meaning their columns represent independent directions. The diagonal of `\(S\)` contains the eigenvalues, which tell us how much variance is captured by each principal component. This decomposition is powerful because it transforms thousands of genes into a smaller number of interpretable axes of variation. --- ## PCA for gene expression - Columns of `\(V\)` are - Principle components - Eigengenes/metagenes that span the space of the gene transcriptional responses - Columns of `\(U\)` are - The “loadings”, or the correlation between the column and the component - Eigenarrays/metaarrays - span the space of the gene transcriptional responses - Truncating `\(U\)`, `\(V\)`, `\(D\)` to the first `\(k\)` dimensions gives the best `\(k\)`-rank approximation of `\(X\)` ??? The columns of `\(V\)` correspond to the principal components — these are often called eigengenes or metagenes because they represent patterns of coordinated expression across the samples. The columns of `\(U\)` give the loadings, which tell us how much each gene contributes to each principal component. By keeping only the first `\(k\)` components — that is, truncating `\(U\)`, `\(V\)`, and `\(S\)`, we get the best possible rank `\(k\)` approximation of our original data. In practice, this is how PCA reduces dimensionality while retaining most of the biological signal. --- ## Alternative Formulation **Least Squares Perspective:** PCA minimizes reconstruction error: `\(M_{PCA} = \arg\min_M \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \Vert x_i - \hat{x}_i \Vert_2^2 = \arg\min_M \frac{1}{n} \Vert X - MM^TX \Vert_F^2\)` where `\(\hat{x}_i = MM^Tx_i\)` is the reconstruction and `\(\Vert \cdot \Vert_F\)` is the Frobenius norm **Distance Preservation:** Given pairwise Euclidean distances `\(d_{ij}\)` between high-dimensional points `\(x_i\)` and `\(x_j\)`, PCA minimizes: `\(\phi(Y) = \sum_{ij}(d_{ij}^2 - ||y_i - y_j||^2)\)` where `\(y_i\)` are low-dimensional representations ??? Another way to think about PCA is as a reconstruction problem. We look for a low-dimensional representation that allows us to reconstruct the original data with as little error as possible. The formula highlights that PCA chooses the projection matrix that minimizes the squared reconstruction error. You can also view PCA as an embedding that tries to preserve pairwise distances between samples. When we project high-dimensional gene expression profiles down to just a few components, PCA seeks to keep the geometry of the data intact as much as possible. This dual perspective — reconstruction and distance preservation — helps explain why PCA works so well. --- ## Geometry of PCA **Loading Vector `\(\phi_1\)`:** - Defines a direction in feature space along which data vary the most - This is the first principal component direction **Principal Component Scores:** - Project the `\(n\)` data points onto direction `\(\phi_1\)` - Scores `\(z_{11}, ..., z_{n1}\)` are the new coordinates - These are the actual values of the first PC for each observation ??? Geometrically, PCA finds directions in the high-dimensional gene space along which the samples vary the most. The first loading vector, `\(\phi_1\)`, is the direction of maximum variance. When we project our samples onto this direction, we get the first set of principal component scores — essentially new coordinates for each sample. These scores represent where each sample lies along this major axis of variation and are what we typically plot to visualize sample relationships. --- ## Geometry of PCA **Further Components:** - Second PC has maximal variance among all combinations **uncorrelated** with `\(Z_1\)` - Constraining uncorrelation ≡ constraining `\(\phi_2\)` **orthogonal** to `\(\phi_1\)` - Principal component directions are ordered sequence of right singular vectors - Variances = `\(\frac{1}{n}\)` times squares of singular values ??? After identifying the first direction of maximal variance, PCA looks for the next direction that explains the most remaining variation while being completely uncorrelated with the first. This requirement of uncorrelatedness translates geometrically into orthogonality — each new component must be perpendicular to the previous ones. The principal component directions come directly from the right singular vectors of `\(X\)`, and the variance explained by each component is proportional to the square of the corresponding singular value. This sequential, orthogonal construction is what gives PCA its clean and interpretable structure. --- ## Variance Explained The proportion of total variance explained by the `\(k\)`-th PC: `$$\frac{\lambda_{k}}{\lambda_{1} + \lambda_{2} + ... + \lambda_{p}}$$` **Interpretation:** - If first 2 PCs explain 80-90% of total variation - Can reduce `\(p\)` variables to 2 PCs without much information loss - Critical for deciding dimensionality reduction **Number of Components:** - There are at most `\(\min(n-1, p)\)` principal components - Most applications use far fewer ??? The fraction shown gives the proportion of variance explained by component `\(k\)`. Often, the first one or two components explain a large share of variation, making it possible to visualize and interpret complex datasets in just two dimensions. In practice, we examine cumulative variance plots to decide how many components to retain. Also note that the maximum number of principal components is limited by the smaller of the number of samples minus one and the number of genes. In gene expression data, because we usually have far fewer samples than genes, the number of PCs is sample-limited. --- ## How Many PCs to Keep? If we keep all `\(p\)` PCs → no dimension reduction If we keep too few PCs → lose important information **Guidelines:** 1. **Variance threshold:** Keep PCs explaining 80-95% of variation 2. **Kaiser's criterion:** Keep components with eigenvalue ≥ 1 3. **Cattell's scree test:** Find the "elbow" where eigenvalues level off 4. **Examine biplots:** Check if separation occurs between groups --- ## Data Example: SNP Analysis Using the `prcomp` function with SNP genotype data: ``` r # Load filtered genotype data load("geno_data.rda") dim(filtered_geno_data) ``` ``` ## [1] 1093 4929 ``` ``` r filtered_geno_data[1:2, 1:6] ``` ``` ## sample_name population super_population rs307377 rs7366653 rs41307846 ## 1 perfect OPT OPT 0 0 0 ## 2 HG00096 GBR EUR 2 0 1 ``` ``` r # Create numeric matrix with SNP values data <- as.matrix(filtered_geno_data[, 4:ncol(filtered_geno_data)]) # Run PCA (limit to 20 components) pca <- prcomp(data, center=TRUE, scale=FALSE, rank.=20) ``` **Note:** Data should be centered; scaling depends on application --- ## Data Example: Variance Explained ``` r summary(pca)$importance[, 1:6] ``` ``` ## PC1 PC2 PC3 PC4 PC5 PC6 ## Standard deviation 9.179448 8.12849 3.31945 2.659811 2.312207 2.211816 ## Proportion of Variance 0.092680 0.07268 0.01212 0.007780 0.005880 0.005380 ## Cumulative Proportion 0.092680 0.16536 0.17748 0.185260 0.191140 0.196520 ``` Shows: - Standard deviation of each PC - Proportion of variance explained - Cumulative proportion Even if first 2 PCs don't explain large proportion, they may still reveal structure --- ## Data Example: Visualization ``` r library(ggplot2) library(ggfortify) autoplot(pca, data=filtered_geno_data, colour="super_population") ``` <!-- --> - Plot shows decent separation of populations - Even with modest variance explained, biological signal emerges - Color by population reveals genetic structure --- ## Data Example: Scree Plot ``` r screeplot(pca, type="lines") ``` <!-- --> - Visual inspection shows elbow at component 3 - Suggests 3 PCs are sufficient - Trade-off between simplicity and information retention Here is a clean Xaringan slide explaining the structure of a **`prcomp`** object, based on your example `str(pca)` output. You can paste this directly into your presentation. --- ## Structure of a `prcomp` Object When we run PCA with `prcomp()`, the result is a list with several key components: ``` r > str(pca) List of 5 $ sdev : num [1:1093] 9.18 8.13 3.32 2.66 2.31 ... $ rotation: num [1:4926, 1:20] 0.00482 -0.00154 -0.00058 -0.03481 0.0011 ... ..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2 .. ..$ : chr [1:4926] "rs307377" "rs7366653" "rs41307846" "rs3753242" ... .. ..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ... $ center : Named num [1:4926] 1.91766 0.04026 0.01921 0.40897 0.00732 ... ..- attr(*, "names")= chr [1:4926] "rs307377" "rs7366653" "rs41307846" "rs3753242" ... $ scale : logi FALSE $ x : num [1:1093, 1:20] -1.63 -2.06 -2.57 -2.68 -2.05 ... ..- attr(*, "dimnames")=List of 2 .. ..$ : NULL .. ..$ : chr [1:20] "PC1" "PC2" "PC3" "PC4" ... - attr(*, "class")= chr "prcomp" ``` --- ## Structure of a `prcomp` Object * **`sdev`** * Standard deviations of each principal component * Length = number of components * Variance of PCₖ = `sdev[k]^2` * **`rotation`** * A `\(p \times K\)` matrix of **loadings** * Rows = genes/SNPs/features * Columns = principal components * Each column is an eigenvector (unit length) ??? * `sdev` tells us how much variance each PC captures. Students should know that squaring these gives the eigenvalues. * `rotation` contains the **loadings**—the weights for each feature that define each principal component. These correspond to eigenvectors of the covariance matrix. --- ## Structure of a `prcomp` Object * **`center`** * Mean of each feature before PCA * Length = number of original features * Used for reconstructing original data * **`scale`** * Scaling applied to each feature * Either `FALSE` or a vector of scaling factors * **`x`** * A `\(n \times K\)` matrix of **scores** * Rows = samples * Columns = principal components * Coordinates of samples in PC space ??? * `center` and `scale` are kept because PCA needs to remember how the data were preprocessed. This is important when projecting new samples later. * `x` is typically what we visualize in PCA plots; these are the sample coordinates in the reduced space. --- ## PCA Drawbacks **Scalability:** - Covariance matrix size ∝ dimensionality - Eigenvector computation infeasible for very high-dimensional data - SVD methods can help but still challenging --- ## PCA Drawbacks **Distance Focus:** - Cost function emphasizes retaining large pairwise distances - Small pairwise distances often more important for structure - May miss local relationships --- ## PCA Drawbacks **Linearity Assumption:** - Orthogonality constraints may not match data generation process - Resultant matrices may lack biological relevance - Non-linear methods (t-SNE, UMAP) may be better for complex structure --- ## When NOT to Use PCA - When orthogonality constraints don't match biology - When local structure matters more than global variance - When interpretability of components is critical - When non-linear relationships dominate - When dealing with highly sparse data (some genomic applications) --- ## PCA Alternatives - Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) - Independent Component Analysis (ICA) - t-SNE (t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding) - UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) <!--- ## Key Takeaways 1. PCA finds orthogonal directions of maximum variance 2. Unsupervised method revealing data structure 3. Requires full-rank matrix for exact solutions 4. Powerful for visualization and noise reduction in genomics 5. Choose number of components based on variance explained and scree plots 6. Be aware of limitations: linearity, scalability, distance focus 7. Consider alternatives when PCA assumptions don't match your data ## References - Applied Multivariate Statistical Analysis (6th ed.), Johnson & Wichern - http://setosa.io/ev/principal-component-analysis/ - Wikipedia: Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors -->